Sanctuaries is a documentary work with several chapters based on stories of reconstruction.

This “residence on earth”, to use the title of a collection by Pablo Neruda, is sometimes strange, often difficult, and it's when things get complicated that human beings show a rage for life that comes from within, and which sometimes resembles a miracle.

What I want to talk about here is the aftermath of the storm, the moment when you have to gather your strength to avoid going under. How do you rebuild?

For this selection, here are three such stories:

Heidie escaped a destructive relationship thanks to Gaëtan. She wanted to regain custody of her daughter and rebuild a stable life. She lives with her bipolar disorder and addictions.

Héloïse, after years of bullying at school, has built a glamorous, fairytale world in her caravan on the family farm.

Philippe is a farmer. Following legal problems, he has fallen deeply into debt. His garden soothes him. His daughter Élisa has moved back in to support him.

Each of these stories is first and foremost the fruit of an encounter. I meet people by hitchhiking in France, and wandering around towns. I ask people if they'd be willing to tell me their stories.

Sometimes a miracle happens: people agree to open their doors and their hearts to me. So it becomes a long-term job, punctuated by regular visits to people's homes over several months.

What unites all the individual stories in Sanctuaries is the energy that pushes all the protagonists out of their violent histories towards light and healing. This work is an ode to hope.

The starting point is my admiration for the life force of these human beings. They are stubbornly seeking a little peace. They seek to free themselves. These battles take place silently in the depths of the day. Very often, the refuge is others, love, bonds. Sometimes romantic, sometimes familial. Sometimes, in Héloïse's case, it's a revival of self-esteem.

« This daily miracle reminds me that, however degraded the world may be, however corrupted or debased humanity is supposed to be, the world doesn't stop being beautiful. It just can't help itself. »

Nick Cave, Faith, Hope, and Carnage

Heidie and Gäetan

Heidie and Gäetan and I met at the end of September in an alleyway in Foix. It was getting dark, and the air was mild.

The first time I saw them, they were embracing on a bench, a little drunk, looking as if they were floating in a kind of cotton called love or happiness.

Their bliss is obvious.

Heidie speaks, Gaëtan looks on. She tells how they've just escaped, and they feel like they're on the run.

Heidie has run away, as she says, from a destructive relationship that lasted several years. She had a baby with this man, a little girl. The baby has stayed with the father, for the time being. Her drunkenness is also a release after years of confinement.

What made Heidie decide to leave was Gaëtan, the young man sitting opposite her, eating her with his eyes. It was the strength of being two, of not being alone. As Heidie says, she needs a man in her life.

She tells the story of how they met: she was shopping and Gaëtan was working in the supermarket, and it was love at first sight.

Then everything happened very quickly. They found a cheap mobile home in a campsite a hundred kilometers from their village, and started all over again.

From that evening onwards, Heidie lets me into her life, photographing the fragility of a period when everything is to be done, but everything threatens to fall apart:

their budding and spirited love, the months-long lawsuit against her daughter's father, the stress of finding money, Gaëtan's withdrawn license, the thousands of kilometers driven all over the Ariège to and from work, to visit her daughter for a weekend or a day.

As the months go by, their love story holds together despite the jealousy, the arguments, the anguish of not seeing his daughter grow up and the immense fatigue of these days.

Heidie's brain often boils, she gets up very early to work at the bakery, she works a lot and her bipolar disorder turns emotions into pressure cookers ready to explode. She also thinks a lot about her daughter, but doesn't see her much. Heidie once told me that she felt like a tightrope walker, constantly between the wire and the void.

What gives refuge is the power of the love between Heidie and Gaëtan. They are bound together with the strength of people convinced that the world is against them.

Héloïse

I met the Iriberri family at Estaing lake in the Pyrenees.

Héloïse Iriberri appeared: sheltered under a denim jacket stretched like an umbrella. Dressed in a long, dark dress, her heeled boots sinking into the damp earth, we all turned our heads in disbelief. It was a funny contrast: her like a fairy in our midst, a muddy, dripping crowd.

I was discovering the Hélose effect.

Her mother, Pauline, was shearing her sheep. She invited me to come and stay with them in La Réole when the transhumance was over.

Héloïse had dropped out of school after being bullied for a year and a half. Following this period, she created an imaginary world of glamour and glitter from her caravan, which serves as her bubble room in the middle of the family farm. This magical world is at odds with the reality all around: farm life, with ewes to milk, cheese to make, pigs to kill, backaches and soaking wet puppies.

This is probably Héloïse's last year before moving to Paris. A few months to build up her confidence, a year to give a definitive damn about what the neighbors, the villagers and the world think, and then maybe to fly away.

This series was shot behind closed doors on the family farm.

Philippe and Elisa

Philippe and I met at the village bar in Lasalle.

The first thing I see of him is his dog. In the half-light at the far end of the bar, monstrous, at the master's feet, drooling in long streams on the tiled floor. I approached Philippe because of his face. He finished his pint, then said come home if you like.

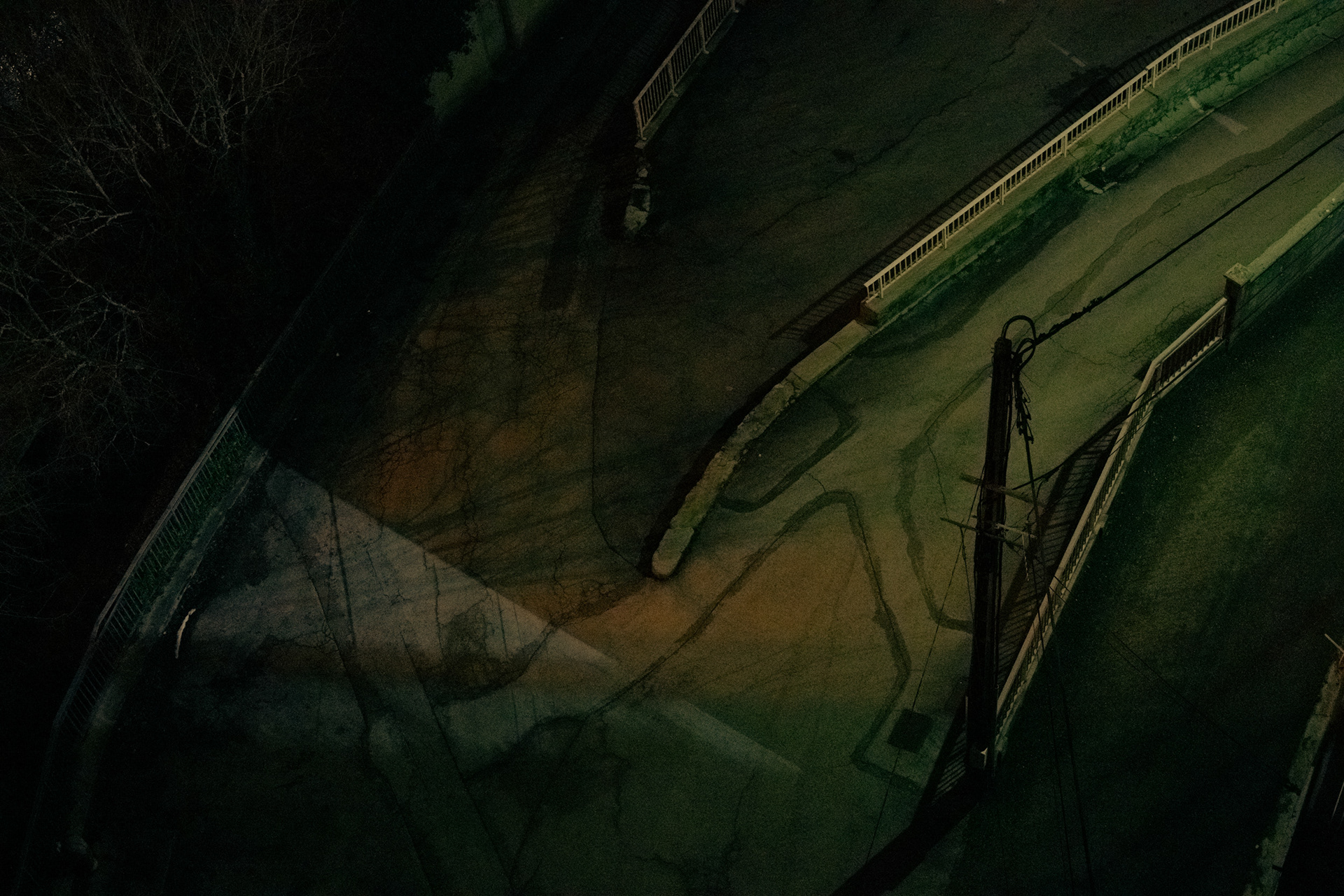

In the car, I tell him I'm afraid of the dog. He laughed a lot. He says there are two others at home, Corsican guard dogs, they won't be mean if you're with me. We arrive on the road leading to the field, and the dogs are already barking as they run around the car.

Philippe is a farmer.

Elisa, his eldest daughter, has moved back in with him, sensing that her father is wavering. The tractor has broken down, and money matters are becoming increasingly burdensome, with lenders piling up. There are days when Philippe shrouds himself in a cloak of silence, his face closed, his gaze unfocused.

The truth is, we don't know each other very well yet. I've only been to see them twice.

Yesterday he said “my sanctuaries are my daughters and my garden”.